The Mukden Incident had erupted in the northeastern China in September 1931, and in October of that year, only a month after the incident took place, a volunteer youth group in Tokyo (Meguro-ku Komaba Seinen-Dan) began a public fund-raising campaign to support the military actions in China. Their objective: to buy a warplane. Yes, these young patriots started the campaign to buy a warplane and to donate it to the Army. It was not even a war bond. They were asking one Sen (equivalent of a dime today, maybe?) from each person they encountered (and possibly visiting neighborhood homes), and eventually two planes were donated in 1932. One of them, the Junkers K-37 imported from Sweden was named “Aikoku No.1”, which was used as a bomber. Another one, “Aikoku No.2”, the Dornier Merkur, was used for transportation of wounded soldiers. Then, the another campaign to buy another plane began. Then another one. Various local municipalities, private companies, or patriotic groups competed each other to raise money. It didn’t take long for these campaigns to be evolved into a full-scale semi-official fascist charity madness where the “voluntary” meant “you-are-a-traitor-if-you-don’t-give-us-money”. The cost of a plane was in a range of 70,000 to 80,000 yen. The daily salary of an average worker was less than 2 yen. It was ingenious way to exploit the vulnerable without being accused of a big money spender.

In any other countries, this mode of fund-raising seems to be rare. Soviet Union had a similar campaign and so was Communist China, but they cannot beat the level of fanaticism and irrationality of Japanese campaigns. Eventually, more than 7,000 warplanes, – fighters and bombers mostly – were donated to the Imperial Army until the end of war in 1945. More than 7,000.

Oh, I forgot. There was a similar kind of fund-raising for the Imperial Navy.

It seems that the exact total number of the planes donated is not certain. One of the reasons is scarcity of the documents or records. Yuuichi Yokokawa noted in his article about the history of these donated planes [1];

Unfortunately, the records of these donated warplanes are not archived systematically, due to the destruction by bombing during the war or by confusion after the war, or maybe due to the fear of being accused of collaborators.

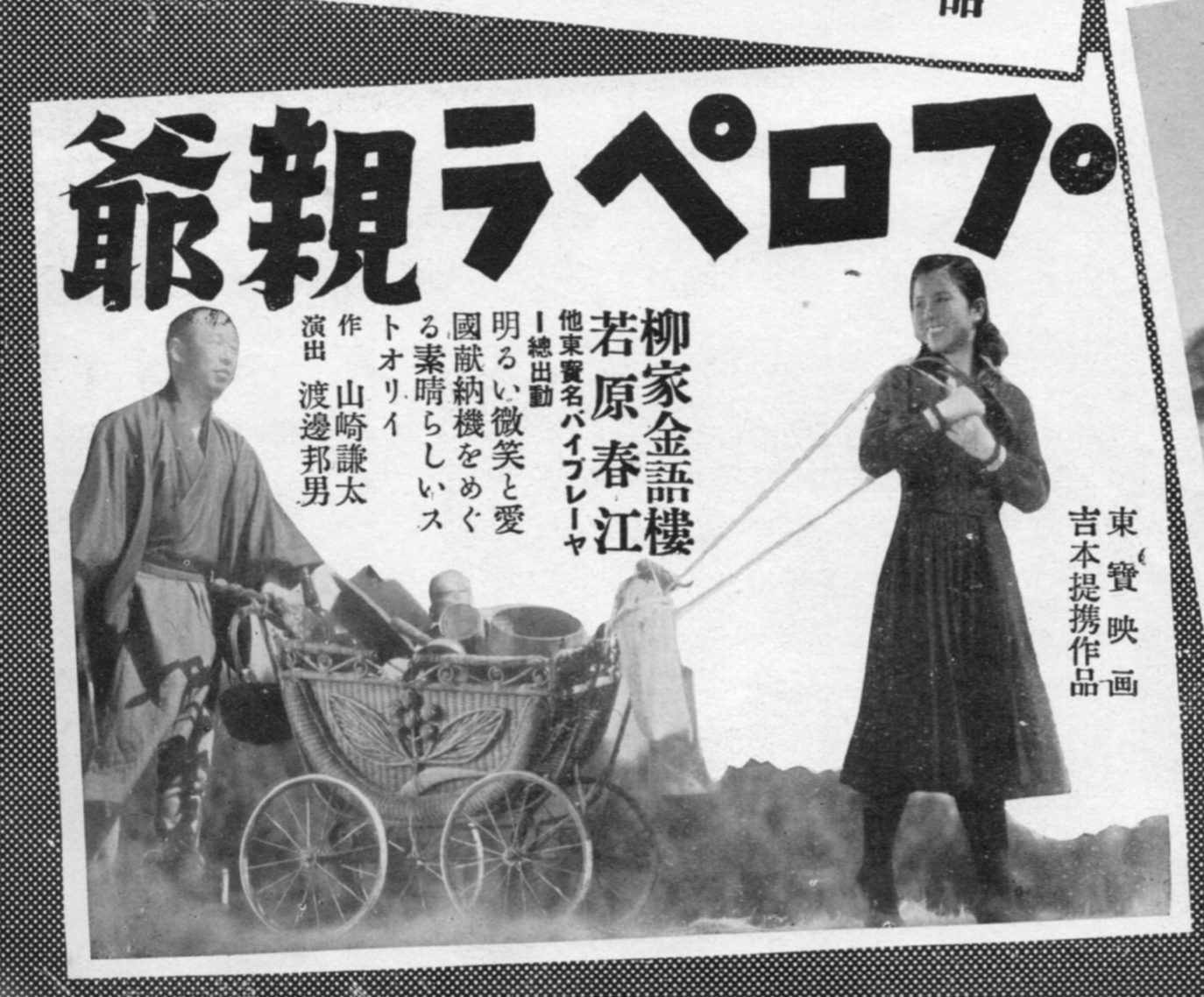

“The Old Man of the Propeller (プロペラ親爺, 1939)” can be seen as a comedic amalgam of “King Lear” and “Christmas Carol”. A neighborhood loan shark is hounded by his relatives expecting big inheritance. But he is not giving any favor to anyone. His only joy of life is to go on junk hunt in the neighborhood, collecting garbages and scraps and selling them to junkmen to make profit. And it’s pretty big profit, too. This old miser actually picks up spilled over beans in front of the grocery store everyday, which accumulated to be barrelful after a year. Then Cordelia enters. His niece, abandoned by her mother, visits his place asking for his assistance. Not much, just to live and to go on. Initially reluctant, but he has no choice but let her stay in his house. Somehow, she enjoys her uncle’s junk hunt, thinking it is for something worthwhile, like donation. His other relatives suspect the motive of this young niece and cook up schemes to kick her out. Then the niece tells a news reporter that she and her uncle are doing the hunt to raise money for a warplane. Now, he becomes the center of all the attention.

The old miser was played by Kingoro Yanagiya, a popular entertainer (rakugo-ka). The film is essentially a showcase of his comedic art – the dead-pan jokes, timing, his Edokko temper, his big bulging eyes, his bold head, etc. – and even though they aren’t funny as they must have been to the contemporary audience, I presume, you still find the finer art of Edo-rakugo sensibility. Kingoro Yanagiya was one of top three comedy stars in Toho studio (the other two were Roppa Furukawa and Kenichi Enomoto) and starred in 4 or 5 movies a year at the time (he would appear in more than 10 movies a year after the war).

The director of the film is Kunio Watanabe, one of the most energetic directors of Japanese cinema. His ultra-efficient filmmaking is legendary. He was the most dependable and reliable speedking, regardless whichever studio he was working for. In the most productive year, he directed 13 movies. The legend has it he directed the 3-part “Daibosatsutoge” in 10 days. As an communist-turned-reactionary, he wasn’t apologetic about his patriotic films during the war in later years. His most successful film was “Emperor Meiji and the Great Russo-Japanese War (明治天皇と日露戦争, 1958)” (trailer here), the first ever film to portray the Emperor by an actor (Kanjuro Arashi). Up until the end of the war, a human actor portraying the Emperor (God) was out of question. Even 10 years after the war, and the New Constitution was in place, it was still a hard bargain and dangerous gamble. When Kanjuro Arashi was approached by Mitsugi Ohkura (Shin-Toho’s Studio boss) and the director Watanebe about the role, Arashi was quite reluctant, saying “(portraying the Emperor) will anger right-wingers and get me into trouble.” To that, Watanebe replied, “I am a right-winger, don’t worry”.

The last of “The Old Man of Propeller” is the scene of the donation ceremony. Solemnly, Kingoro and his niece attend the Shinto ceremony celebrating the completion of the donation and the public display of the brand-new donated plane. Tatsuhiko Shigeno, reviewing this film, noted [2];

The charm of Kunio Watanebe’s works lies in the very smooth plot development. Every bit part (of the film) is never boring. The scene where the military officer is reading the congratulatory address is done away with just one close-up shot. It is said that the actor (who played the officer) never went to the location. What an audacious way of an expression, I thought.

Considering the political undertone of the film – encouraging ordinary citizens to involve in the machinery of aggression -, it must have been rather customary to include military personnel delivering patriotic speech of some kind. And Shigeno is referring to the fact that the director skipped all that pompousness and directly to the scene of the new plane flying over the owe-stuck attendants of the ceremony. This brazen efficiency and lack of pretentiousness is the trademark of Watanebe’s direction. His other efforts (including “Kessen no Ozora-e (To the Sky of Decisive Battle, 決戦の大空へ, 1943)”) were sometimes more blatantly patriotic, though.

As a whole, this film is a completely outdated curiosity. Kingoro’s comedic antics are almost pastoral and amusing, but not funny to us 80 years later. Other characters are the stock players doing their jobs. And the director must have been bulldozing away his project as fast as possible. And that’s what entertainment was all about. But the framework of the moral – purchase of a weapon by ordinary citizens – is so outlandish that the film might look avant-garde to anyone who is not familiar with fascist mentality. Or, it should be outlandish and should stay that way.

The Old Man of the Propeller (プロペラ親爺, 1939)

Directed by Kunio Watanabe

Produced by Teppei Himuro

Wrtten by Kenta Yamazaki

Cinematography by Akira Mimura

Starring Kingoro Yanagiya, Harue Wakahara, Nijiko Kiyokawa

[1] Yuuichi Yokokawa, “Investigative Reports on the Donated Warplanes, the Imperial Army Aikokugo”, Koku Fan, October, 2011 to February 2012

[2] Tatsuhiko Shigeno, Movie Review, “Puropera Oyaji (The Old Man of the Propeller)”, Kinema Junpo, June 1, 1939

Copyrighted materials, if any, on this web page are included as “fair use”. These are used for the purpose of research, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s).