Along the east bank of the Arakawa river in Tokyo, there is a place called Yotsugi. The place is a part of Katsushika, the lower town of the metropolis. Today, this neighborhood looks as generic as any other residential area, but rather chaotic web of narrow streets tells you the place has been developed with little total grand design. In 1930’s, the place was filled with rows and rows of flimsy, jerry-built tenements for low-income families.

Masako (Hideko Takamine) is a 6th grader in the elementary school in this district. Her family is one of the poorest even in this underprivileged neighborhood. Her father is a tinsmith frequently out of work. In this rather harsh environment, she finds a joy in writing. Her teacher (Osamu Takizawa) encourages her to write compositions in more realistic style, commenting “write what you saw and experienced as exactly as they were”. Her frank description about her life, family and small incidents in her small world impressed many adults, and eventually one of her essays is published in the popular magazine. That’s when the world, the world of grownups, slaps her so hard.

The film is based on the book “Tsuzurikata Kyositu (綴方教室, Composition Class)” by Masako Toyoda, a model of Masako in the film. In fact, the book itself was a collection of essays (compositions) Masako Toyoda had written in her composition class a few yeas earlier. The instant bestseller was considered as an evidence for success of the Japanese modern education system and Masako Toyoda was hailed as a girl wonder. At the time of the film’s release, Masako Toyoda was 16 years old.

Miekichi Suzuki (1882 – 1936) was an influential and energetic writer in the field of children’s literature. He published “Akai Tori / Red Bird”, probably the earliest and the most prominent monthly magazine of children’s literature since 1917 until his death in 1936, 196 issues in total. Suzuki considered that children need to be exposed to more imaginative and more perceptive writing than what they read in school textbooks or children’s books at the time.

“Red Bird” is a pioneer of the most influential movement to expel the today’s uncivilized, vulgar reading materials for children and to develop purity of the young. So we collect the sincere efforts by the first-rate artists of today, and to welcome the emergence of the creators for young children.

Motto, Red Bird

The magazine published some of the finest short stories and poetries by Ryunosuke Akutagawa (The Nose, Tu Tze-chun), Hakushu Kitahara (Suzume no Oyado), Kan Kikuchi, Toson Shimamura and Miekichi Suzuki himself. The movement was successful and enthusiastically welcomed by school teachers. Suzuki pushed the movement further, encouraging children to write compositions in more intuitive, naturalistic style, rather than the rigid and unimaginative style taught in schools since 19th century.

Look at the compositions by young children today. Look at the compositions selected by adults as a standard. Children and adults are completely poisoned by the vulgar writings of today, found in newspaper or magazine articles. “Submitted Compositions” selected by Suzuki in “Red Bird” is the agency to show examples of what the true writing is to all the children, to the people who are responsible to children’s education, and to all the other people.

Motto, Red Bird

Suzuki encouraged the writing in naturalistic and realistic styles – “write as you saw it, as you heard it, as you felt it” to express “pure feelings” of the young children. Young teachers considered Suzuki’s approach more refreshing and promising than the antiquated composition methods, and encouraged their pupils to write their lives as they were. Masako’s teacher (Ohki) was one of the believers of Suzuki’s philosophy and he instructed the class to write compositions in realistic, perceptive style. Surprised by Masako’s talent, Ohki submitted her composition to Red Bird, which eventually published many of Masako’s compositions. Her compositions were collected and published as “Tsuzurikata Kyositsu” in 1937. The popularity of her book and a flood of praises it received were not only the proof that Suzuki’s progressive ideas worked, but also the evidence that the modern democratic education system actually worked. Since Masako’s family was living in the deepest bottom of the poverty, her composition naturally depicted the depressing facts of life – her father losing a job, nothing to eat, the bicycle was stolen, etc. The very fact that an impoverished girl wrote a series of refreshingly naturalistic essays, not a privileged young boy from upper crust with a promised future, inspired many teachers and parents.

The film was produced under the same philosophy as Red Bird. It was shot mostly on location, with strong emphasis on details of poverty. In fact, when her father tells how his bicycle was stolen, it is hard not to draw comparison with “Bicycle Thief”, the masterpiece of Italian Neo-realismo. In both films, the ownership of a bicycle is significant, more in economic terms, but so significant that its loss could cripple the already desolate household. The difference in approach is quite revealing though: In the Italian classic, the theft of the bicycle and the subsequent father’s demise are the focal points of drama. It is dynamic and life-changing experience for the father and the son. In “Composition Class”, however, it is more like an essay.

When I visited Mr. Hirata’s home, Mr. Hirata ain’t home, went to the bathhouse. When he’s gone to the bathhouse, he’s gone for a long time, so I was waiting in the living room, sat close to the stove and chatting silly stuffs with Mrs. Hirata. Then after an hour or so, Mr. Hirata came back and I got paid, then when I opened the entrance door, you know, I immediately got that feeling … You know, my bicycle was gone.

Masako’s father (Musei Tokugawa) tells this story in a pathetic voice, knowing he is to be blamed for not being careful. Masako’s mother (Nijiko Kiyokawa) crucifies him. A series of insults are sputtered by the exhausted mother, and the father protested in almost inaudible voice. It does not transform the family’s life. It just pours a load of salts to the open wound.

Though “expressing as you saw it” may be a grand motto, we all know there is always an inconvenient truth. In one of her compositions published in Red Bird, Masako wrote that one of her neighbor remarked “Mr. Nemoto is stingy”. She wrote as she heard it. Well, Mr. Nemoto may or may not be stingy, but he was the Masako’s father’s employer. The resentment and worries broke loose in the neighborhood. Probably you have a similar experience. I do. When I was a kid, I said something that I didn’t think it was a big deal, and it was a big deal. It was a big deal to people older than 30 around me. “But I said what everyone is saying !” wasn’t good enough defense against the case where the verdict was already delivered. “Guilty on the first degree public blundering !” “But …” “Kid, go wash your mouth.” Advocating children’s purity is one thing. But a child is also a part of the society. The world goes around and certain things are better left unsaid, some say. Then this goes straight to the core of the dilemma in the realism. In “Composition Class”, we see unflattering depiction of poverty, incredibly wide gap in social awareness, and the lives of the underprivileged. But how much of it are ‘true’? Or ‘real’? Since Masako realized writing certain things was not appropriate, there might have been many things and events left unwritten. The teachers, the editors and the publishers might have edited out certain things. The filmmakers, the producers and the censors might have cleansed the world photographed on the film. The poverty we see up on the screen may be a version of poverty some people wanted us to see, or a reflection of what we wanted to see.

Hideko Takamine was 14 years old at the time, but her acting here is already exceptional. Subtle changes in her eyes and tone of her voice speak more eloquently. According to her biography, she was already supporting her family at the time. Her family, including more blood relations you can think of, decided to take advantages of her as much as possible. In her own words, she had become a mere “money manufacturing machine”, giving up schools and a normal life as a teenager.

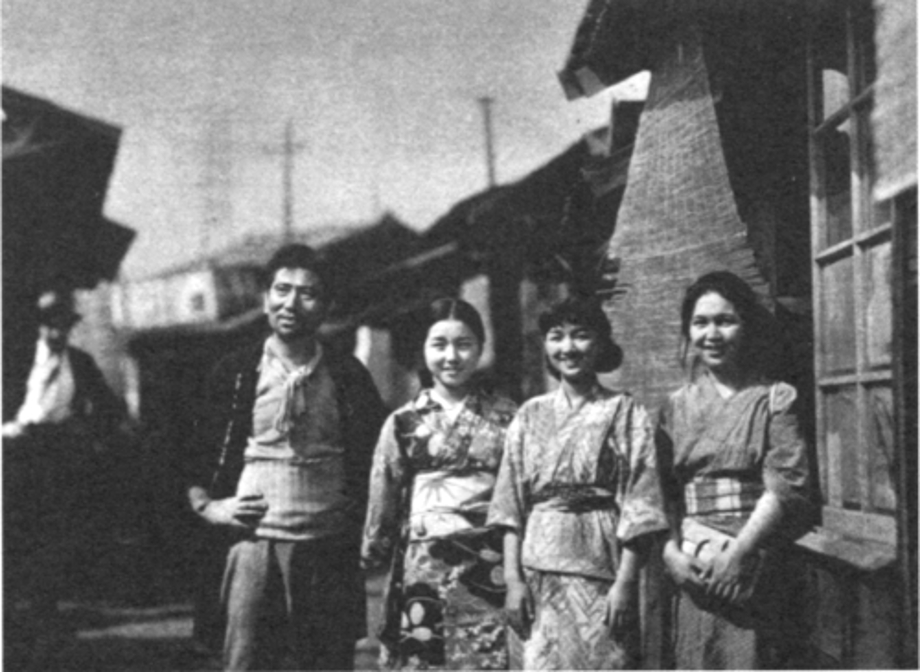

When Masako Toyoda visited the studio during the production of the film for the publicity, a bit of a feud between these two teenage girls erupted. According to Toyoda’s account, Takamine was looking down on her, suggesting Toyoda must be envious about the life in the movie studio, coming from such a poor family. Takamine’s account was somewhat different. She thought Toyoda was not acting honest, or rather pretentious. “I was poor myself,” Takamine said.

The film’s director, Kajiro Yamamoto, was one of the most popular and successful filmmakers in 1930’s and ’40s. Though his career went somewhat sour after the war, he was a good mentor to many young filmmakers. Akira Kurosawa, Ishiro Honda (Gozilla), and Senkichi Taniguchi (Snow Trail) were all assistant directors under Kajiro Yamamoto, learning everything from writing scripts to audio overdub. In “Composition Class”, Akira Kurosawa is billed as “Chief Production Director”, probably meaning the chief assistant director. During the later scene in the film, pouring rain floods the muddy land of the poor tenements, accentuating the sorry state of their lives. Probably I am not the only one to see poetic resemblance of the scene to the battle scene in Seven Samurai.

The contemporaneous reviews are somewhat unenthusiastic, though admitting its box-office appeal. Tomoda Junichiro remarked many of TOHO’s actors and actresses didn’t look convincing as people living in the slum, commenting “even Nijiko Kiyokawa looked sophisticated under this condition”. Since I was of the opinion that Kiyokawa was particularly convincing as a wary, exhausted mother of three little children, I was surprised by this comment. Maybe, I am fooled by the beautification of the reality by the know-it-all adults.

After graduating from the elementary school, with all the success she had in composing essays, Masako went to work in the nearby factory. Yotsugi factory of Nihon Seichu was one of the oldest factories around, manufacturing ropes, threads and laces. During 1930’s one of its most important products was ropes for parachutes. You know, Japan was invading China at the time.

Composition Class (綴方教室, 1938)

Directed by Kajiro Yamamoto

Produced by Nobuyoshi Morita

Written by Chiio Kimura, Based on the essays by Masako Toyoda Cinematography by Akira Mimura

Starring Hideko Takamine, Musei Tokugawa, Nijiko Kiyokawa, Osamu Takizawa

TOHO

Copyrighted materials, if any, on this web page are included as “fair use”. These are used for the purpose of research, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s).

Pingback: Kajiro Yamamoto | Enic-cinE