This is part two of “Films of 1949” series. (Part 1 is here)

“Crape Myrtle always brings bad luck.”

Until I saw Kurosawa’s “Stray Dog”, I had never heard of Crape Myrtle being the omen of bad luck. This line occurs as a part of the audio montage during the pivotal scene in the film. A woman was brutally murdered in a quiet house in upper-class neighborhood. Her husband, a well-to-do businessman, Nakamura, had been away on a business trip, The Police was working on fingerprints and other clues in the murder scene, ransacked by the murderer. They knew instinctively the weapon used in the crime, though; the Colt automatic stolen from the young detective (Toshiro Mifune). Neighbors curiously peering into the house, exchanging whispers. How chummy the Nakamura’s were, and it is that house with Crape Myrtle. This superstitious whisper made lasting impression on me.

Crape Myrtle has been and still is one of the popular garden trees in Japan, due to its ease of care and its relatively compact size. By all means, its gorgeous blossom would stand out in all-green neighborhood during humid heatwave in August. Then, how come some consider it as a bad omen?

The meaning and timbre of the word “Saru-suberi”, Japanese for Crape Myrtle, do cause slight uneasiness on our linguistic nerves. Its literal meaning is “Monkeys slip” or “Slippery (even) for monkeys”, referring to its smooth surface of its bark. This “slip” leads to “slip in business or in life” in general, as they say. Another reasoning for superstitious belief is that Its blossom falls by its neck when it’s done and some associate it graphically with beheading.

However, upon close examination, the scene is a bit of a puzzle. I am not able to place actual “Crape Myrtle” in Nakamura’s house. There are several shots of the house in the sequence. First several introductory shots (piano soundtrack in background) are definitely not Nakamura’s house. It is there to show that the story about to unfold is in an affluent neighborhood. Then, as the tone of soundtrack turns grim and solemn, the sequence of shots captures a group of spectators gathering around the crime scene,as the uniform policemen guard the area. There are small kids, a frightened young mother and a couple of men talking to officers. Then, the shot of the house. It introduces us to Nakamura’s house. Some pine trees and rose bushes are visible, but I cannot spot a single tree of Crape Myrtle. So where is the tree in question? In fact, one tree of Crape Myrtle can be seen, exactly when the whisper referring to it is on audio track. It is a tree behind the group of people peering at Nakamura’s house. Then, if this superstitious man is referring to that Crape Myrtle, he is talking about the wrong house.

It might well be one of technical “goofs” created in editors’ room. However, it is rather puzzling since the audio track must have been inserted later than construction of visual montage. Kurosawa and Goto (the editor of the film) didn’t get the necessary shots, maybe. I really cannot tell. But I am quite sure that the slight inconsistency in logic was not of concern here for Kurosawa. To him, it was this lasting ringing of the whispering voice that mattered.

There is another reference to botanical mise-en-scene in this sequence. Tomatoes.

My wife…planted these tomatoes. The day I left town, they were still green.

But now that I’m back, they’ve all ripened and turned red, even though my wife is dead.

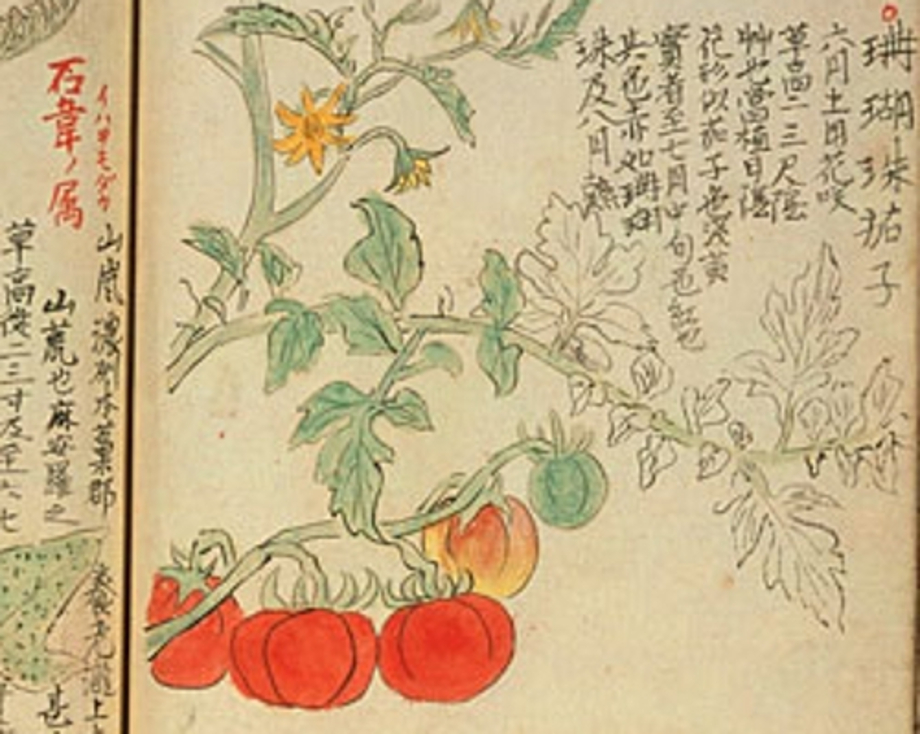

The shots of tomatoes, squashed on the ground, are cross-cut with the terrified gaze of Toshiro Mifune. Though it is one of the most popular vegetables today, both in markets and in gardens, I didn’t know if tomato was recognized by general public as a part of everyday food in 1949.

General history of tomato in Japan tells us that it was first introduced to Japan during Edo era and remained relatively unknown to general public throughout Meiji and Taisho eras. Popularity of the Western cooking in the later years made many foreign vegetables visibly available in market. So I assumed tomato must have been one of those foreign vegetables, making this episode sharper on social comment. Nakamura, apparently well-to-do for 1949, could afford luxury of enjoying little gardening, with some exotic vegetables such as tomatoes.

A bit of research revealed tomato was not as exotic in 1940’s Japan at all. It is one of the most popular home grown vegetables since early Showa era. During the war years, tomato had been promoted as one of the easy-to-grow fruits, and apparently many families planted it in their small gardens to fill in their ever-scarce food supply. Then, the connotation of tomato in this context is far from nouveau riche’s pastime. Visual sensation of squashed tomato is extremely visceral, of course, but another underlying implication, tomato as a popular gardening vegetable among general public, may have different imagery among the viewers at the time.

Tomato frequently pops up in novels, prose and poetry of pre-war to post-war generation. The most notable example in the early Showa era can be found in Kenji Miyazawa’s “The Night on the Galactic Railroad (1934)”, a splendidly atmospheric fantasy. Early in the novel, Giovanni has a dish of tomatoes for his lunch. His sister prepared it for him and left it on the window sill. There is a mention of Kale and Asparagus grown in the box as well. Miyazawa was an ardent student of agriculture and believed that community of rich (and scientific) agriculture is the paradise. He injects variety of vegetables, crops, and other plants into his novels, in hopes to make them known to public. During the same period, Santouka Taneda, known for a variety of free-style Haiku, compose one with eggplants and tomatoes, rejoicing the rich harvest in summer time. Stark contrast of red, green and dark blue under intense rays of sunshine creates joyous melody of life.

The war years turned this cheerful memory of the vegetable to sour. sometimes tragic ones. In Osamu Dazai’s short story, his wife’s garden is mess, and tomato is one the victims. It seems it is not about an actual garden, but rather about the state of his mind at the time. Osamu Dazai is still one of the most influential postwar Japanese novelist (though his works extends back to prewar years), and his works represent the languished identities of Japanese people by the war and its aftermath.

Hiroshima pops up a couple of times when looking for the presence of tomato in war years. My wife told me the story she had read, about a group of young doctors who were sent to devastated Hiroshima. Words about “toxic” water were spread throughout the city and young doctors were warned of possible contamination from “The New Bomb”. To avoid dehydration under intense heat, they turned to tomatoes still standing in the barren land. It turned out, these vegetables were also contaminated. They would suffer long-term ailment due to internal radiation poisoning. There are several accounts of tomato and dying children in Hiroshima aftermath. “Machinto” is childrens’ book about a three-year old girl craving for tomato while suffering from massive radiation. Her mother desperately searches for tomatoes in the city, finally finds one in a local shop, but too late. The child is gone. Another private account of the apocalyptic Hiroshima relates the story of a teenage girl dying. She suffered serious burns and bleeding. She was also craving for water and her father told her kid brother to pick a couple of tomatoes from their back yard, squeeze them to make juice. The kid brother soaked swabs into fresh liquid and gently dripped juice on her lips. Tomato was her favorite food, and kid brother realized his father knew she wouldn’t make it.

As for Crape Myrtle and Hiroshima, Tamiki Hara mentions it in his Haiku anthology “The Atomic Bomb”.

Heat of Sun, Full of smell of Death, Crape Myrtle

Crape Myrtle and Tomato are both full of life in summer. In full bloom of gorgeous pink or ripen to pure red. Such burst of energy of life is nature’s irony to numerous deaths and unimaginable agony not only in Hiroshima but throughout Asia in summer of 1945. The memory of August 1945 was etched in people’s mind, suffering with no end, burnt soil, more death and a lot more. Survivors in 1949 might find traces of that August in Crape Myrtle and tomato.

Then, that whisper, “Crape Myrtle always brings bad luck” echoed more grimly in theaters in 1949 than today.

Copyrighted materials, if any, on this web page are included as “fair use”. These are used for the purpose of research, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s).